Rubén del Valle Lantarón

The world of contemporary art is a polycentric network of mutant and eventful topography where the international circulation is a seductive experience at permanent risk. Tom Wolfe considers it a “statusphere”; Sarah Thornton assures that, “It is structured around cloudy and even contradictory hierarchies of fame, credibility, imagined historical relevance, international connection, education, perceived intelligence, wealth . . . ”

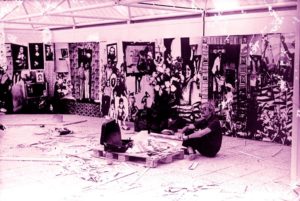

Raúl Martínez montando su trabajo en la Bienal de Venecia / 1984

Since the 1990s Cuba has consciously tried to insert itself into this complicated framework from which we were never completely isolated, but for some decades restricted to very precise and limited conditions. Entering the 21st century, this community of diverse actors has joined the global network of events, exhibitions, museums, and galleries that make up the world of international imagery in its most extended sense. The Havana Biennial played a determinant role, attracting a multitude of critics, experts, museum directors, and gallery owners to the Cuban capital, as well as artists from every imaginable region. They met, interacted, and collaborated on the basis of an unprecedented platform of visibility in those days. Only Euro-centrist Venice (1895), cosmopolitan Sao Paulo (1951), and the distinctive Sydney (1973) organized similar events. Our moment emerged as a Robin Hood crusade that disrupted the established canons between the center and the periphery and granted the Cuban art circuit a horizontal and heterogeneous stage directed by an audience eager to become acquainted with the distinctiveness of our artistic production.

What had Venice and its Biennale been for us up to that moment? It was a chimera, a profound emotion, as pointed out by a certain critic. But not much more. The first presence, almost 60 years after the founding of the event, was presented in Los Jardines (The Gardens) and consisted of 25 paintings by 15 artists (Cundo Bermúdez, Servando Cabrera, Mario Carreño, Sandú Darié, Roberto Diago, Julio Girona, Víctor Manuel, Luis Martínez Pedro, José Mijares, Raúl Milián, Amelia Peláez, René Portocarrero, Mariano Rodríguez, Felipe Orlando, and Rolando López Dirube).1 There were already in those days quite a few diatribes and various complaints. But we had to wait 14 years to return to the ring, and the decision at the time was to present a solo exhibition of René Portocarrero, who repeated against all odds. Six years later, the Italian-Latin American Institute (Spanish acronym IILA), bet on the essential Wifredo Lam and organized a solo show. It took another ten years for Alfredo Sosabravo to get in.

The breakthrough was in 1984. The first edition of the Havana Biennial, coinciding with a Cuban representation in Venice made up by Raúl Martínez, Mario García Joya, and a group of objects in paper mâché from Antonia Eiriz’ workshop, was a turning point in the perception of art and artists. Juan Francisco Elso Padilla at the Arsenal, and Flavio Garciandía as part of the Aperto, covered 1986, while two years later Manuel Mendive captivated in an edition dedicated of the artists’ space. The IILA sponsored the participation of Belkis Ayón and Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal in 1993, of Eduardo Rubén Rodríguez in 1995, and of Roberto Diago in 1997. Harald Szeemann took Alexis Leyva Machado to his Dappertutto Aperto Overall at the 48th Biennale and Tania Bruguera to the Arsenal in the following year. That same year the IILA was committed to Ibrahim Miranda and Luis Gómez. In 2005 Tania participated for the second time, and Carlos Garaicoa and Los Carpinteros for the first, sponsored by the IILA. The next edition featured René Francisco Rodríguez and Wilfredo Prieto, and Garaicoa repeated at the 53rd edition, all sponsored by the IILA. A curious detail is that Ricardo Rodríguez Brey represented Belgium, the country that adopted him at the 47th edition, and Félix González Torres represented the United States at the 52nd.

Note that except on the first two occasions, our presence in Venice was never an official representation. Artists were invited by curators to specific projects and exhibitions, whether central, parallel, or collateral. A new turn is noticeable at the opening of the second decade of 2000, a circumstance that opened the possibility to take up again the national representation model in a sequence that evolved eight years later toward an autonomous pavilion.

De derecha a izquierda: Maria Vicini, Giacomo Zaza y Sandra Ramos durante el montaje de Anarquía de los relatos

The proposal of Italian editors Miria Vicini and Cristian Maretti to organize a Cuban pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale was channeled in 2011 through the Ministry of Culture of Cuba, only a few months before the opening of the exhibition. They formulated a joint showcase of Cuban and Italian artists, and appointed Italian essayist, poet, art critic, and curator Duccio Trombadori in charge. Miria Vicini was appointed curator. She shared that position with Jorge Fernández Torres, director at the time of Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center and director of the Havana Biennial, who was appointed by the Cuban Ministry of Culture.

Thus, the exhibition Cuba Mon Amour was inaugurated in the Pavilion of the Republic of Cuba, in the Caserma Cornoldi of San Servolo Island, with works by Cuban artists Eduardo Ponjuán, Alexandre Arrechea, Yoan Capote, and Duvier del Dago, along with Italian artists Alessandro Busci, Felipe Cardeña, Desiderio, Giorgio Ortona, and Alessandro Papetti.

According to Trombadori, “Cuba Mon Amour . . . best shows the human sympathy, care, and close friendliness of Italian and Cuban culture. Proud of its excellent tradition in visual arts, the island of the “Top Leader” does not lock up its expressiveness in the doctrinaire space of univocal ideological poetics, deprived of individual creativeness. Loaded with irony, tendentious, dreamlike, capable of being self-critical and open to the panoply of the contemporary world, Cuban visual art shows an effervescence with no sign of decadence.”

Referring to the Italian presence he points out: “And it is so that irony, the sense of distance, and the merciless vision of the extreme experiences of western civilization mark a way of making art that links the ethic and aesthetic elements with measure and intelligence. An impetuous opening toward the future emerges with extraordinary enthusiasm for life and culture from lessons not at all ambiguous as these, projected and offered to us once more by the encounter with Cuban hospitality and with the witnesses of its ”artistic will”.

Although the showcase was thought to open a new possibility for the exhibition of Cuban art, in general it lacked coherence in its curatorial conception, with noticeable absence of an organic point of view between the formal and conceptual discourses of the guest artists. While the Italian artists were present exclusively in the fields of painting with pieces that at times appeared chaotic, the Cubans adhered to installation, tending to conceptualism, and with total predominance of the object.

Glenda León / Música de las esferas / 2013

Initially there was an attempt to send works of more contemplative and traditional art. Faced with that situation, the representatives of the Cuban institutions had to shield our positions and firmly defend the intellectual and professional capacity to make decisions exempt from any conditionings. But that neither ensured an integrative result, nor contributed to the creation of at least a concomitant narrative.

That moment, however, had far-reaching importance because it opened a path that had been unavailable for almost three decades toward the consolidation of an active and dynamic Cuban presence in Venice, by way of a National Pavilion. The experiences obtained on that occasion enabled adjustments to the procedures for future editions, promoting unified teamwork among all the parties involved.

The 55th Venice Biennale was announced for 2013. The National Council for Visual Arts and Maretti Editions repeated the Cuban Pavilion, featuring the curator team of Giacomo Zaza and Jorge Fernández, who gave a new conceptual dimension to the project and brought it to the highest level of the event. The Pavilion manager was Miria Vicini, who secured for our Pavilion none other than the National Archaeological Museum in Saint Mark’s Square, in the center of the city. Under the title The Perversion of the Classics: the Anarchy of the Stories, the curators brought together 13 artists (6 Cubans and 7 international), whose personal aesthetics, concerns, and views interact organically among themselves while representing a multi-directional encounter with the history of art among diverse places and times, where the classic and contemporary negate and reconcile each other.

Among the Cubans were María Magdalena Campos-Pons & Neil Leonard (the painter from Matanzas appears with her husband, a musician from the USA), Glenda León, Liudmila & Nelson, Sandra Ramos, Lázaro Saavedra, and Antonio Eligio Fernández (Tonel), in addition to Rui Chafes and Pedro Costa (Portugal), Francesca Leone and Gilberto Zorio (Italy), H. H. Lim (Malaysia), Hermann Nitsch (Austria), and Wang Du (China).

Lázaro Saavedra contra Lázaro Saavedra cargando a Carlos Marx

In his words for the catalogue, Jorge Fernández commented on the showcase: “Our participation could not reproduce that tradition mentioned by Boris Groys when quoting Walter Benjamin, which involves a linear tour of halls and works in analogy to the architecture and equivalent to the sensation received by the spectator when visiting any city. Here we approach that polytheist freedom that Groys himself attributes to the installation. Our curatorship does not construct, it rather dismantles and breaks up spaces. We do not pretend to achieve a structured and logical sequence because that is impossible. The pieces in the halls have to be discovered. They are gestures and footnotes to what you are looking at.”

Setting up this exhibition was a true adventure characterized by the Museum director’s and specialists’ lack of experience dealing with contemporary art. In the end a fertile dialogue was established between the transgressive nature of the artists in the showcase and the Museum’s sacred mission of preserving the enormous heritage it contains. The Art Logistics team played an important role in the entire process, dealing with the insurance and production at the Pavilion, allowing for a high level of staging. Despite the spectacular nature of the project and the effects of the museology inserted in daring counterpoint with the classic paradigms, the fancy catalogue and ample promotion, I am still unsatisfied about the failure to obtain an autonomous pavilion for Cuba. My conversations in this regard with friends and colleagues opened a possibility that was to have a positive result some years later.

The 56th Biennale (2015) had the same work team: Miria Vicini as Manager and Giacomo Zaza and Jorge Fernández as curators. It was held once again on the island of Saint Servolo, this time with the title The Artist between Individuality and the Context. Cubans Luis Gómez, Celia & Yunior, Grethell Rasúa, and Susana Pilar, shared the space with Lida Abdul (Afghanistan), Giuseppe Stampone (Italy), Lin Yilin (China), and Olga Chernysheva (Russia). The curatorial concept assumed as its conceptual axis the figure of the artist, approached from the duality of his individuality and his circumstance, i.e., the artist as decoder of realities, as re-editor of social, ideological, and historical frameworks.

María Madgalena Campos-Pons durante el montaje de su instalación 53 + 1 = 54 + 1 = 55 / Letra del año / 2013

The Cuban showcase chose an intelligent, questioning art, anchored to the concrete reality of Cubans, but with supports and approaches that went beyond the local and inserted themselves into the universal. The exhibited works: We are the Revolution, by Gómez; About Permanence and Other Needs, by Rasúa; Notes on Ice, by Celia & Yúnior; and Immaterial Domain, by Susana, raise global issues along with other themes inherent in the art world such as the predominating double standard in the sector, where a new figure, the artist-media entrepreneur, has emerged. In a way, they suggested a criticism of the system of major events, where what is essential is not the symbolic value of the work itself, but the merchandising that takes place around it. Beyond the exhibition, its thesis, the artists or the works, our presence was maintained as continuation of a valuable promotional operation. However, to some extent the scope expected from those efforts was hampered by deficient and biased advance publicity, the absence of a catalogue, and the scarce information that circulated afterwards.

And success was finally attained in the fourth attempt. When it seemed that these efforts would again fall into the void, luck and persistence helped Enrique Martínez Murillo, director of Art Engineering, find in an old diary the contact information of an Argentinean colleague who lived in Venice. Scarcely three months before the deadline to certify a Cuban pavilion before the event management, and in the company of Isabel M. Pérez, who had been invited to visit the Biennial of Architecture, he toured the lagoon in search of some free space to plant the fatherland’s emblem. The library located at Loredan Palace, belonging to the Venetian Institute of Sciences, Arts and Literature had not made a firm decision about which option to choose. It didn’t take anything else. Scarcely a week later we had succeeded in lowering the rent by 30 percent, generously expand the available space, and discussed the initial plans of possible collaborations, support, and contributions. The complex task of reactivating the machinery took place, giving the curatorial responsibility to José Manuel Noceda, researcher from the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center, who had accepted the invitation from the final days of the previous edition. The National Council for the Visual Arts outlined a general strategy tending to favor the meeting of generations, aesthetics, and procedures that characterizes contemporary Cuban art; maintaining our standard figures of participation up to that point, only this time, finally, it would be only of those born on the Island.

Cuba had its pavilion at the Venice Biennale near Academy Bridge, in one of the most central, spacious, and visited squares of the city. Sixty-five years had gone by since Giovani Ponti, director of La Biennale, invited the Cubans to participate for the first time. Under the pressure of the deadline, Noceda was immersed in the analysis of both the general proposals of this 57th edition of the event, convened under the motto Viva Arte Viva, and the context and peculiarities of the art produced on the Island. His professionalism and experience contributed to the rapid crystallization of an individual focus based on Alejo Carpentier’s thesis on the coexistence of three simultaneous temporary moments in Latin America: past, present and future as times of memory, of intuition and vision, and of the wait.

Tonel en el proceso de Iluminaciones / 2013 / Intervención

Times of Intuition brought together the proposals of Esterio Segura, Roberto Fabelo, Iván Capote, René Peña, Abel Barroso, Mabel Poblet, Reynier Leyva Novo, Meira & Toirac, Wilfredo Prieto, José Yaque, José Manuel Fors, Roberto Diago, and Aimeé García. The name sequence corresponds to one of the possible tours of the showcase in situ. The present issue of the magazine Artcrónica is dedicated to the current editions of Kassel and Venice. There are plenty of interviews, articles, chronicles on the expectations and future of our attendance to both meetings. My comments will be restricted to point out that I evaluate this 57th edition as a successful exercise of cultural policy that reconsiders the normal forms of participation of national pavilions and impregnates the Venetian winds with the mixed and permeable flavors of the national vision. It is an exercise that strengthens us in a context of dissimilar perceptions and which pays tribute to the renovation of the thought once confirmed by the Havana Biennial. Ultimately, it is a selection that appropriated the significant and individual contributions in the symbolic contemporary scene, and not only the latest ones.

The rest is just a drawing in the water.

The periodicity of Venice alternates regularly with that of Havana. We should remember that our Biennial happens (or happened) every three years. Let us then not ignore the fact that when both events coincided the real possibilities of dedicating resources and energy to the Venice event decreased, thus affecting the outcome to some extent. Meanwhile, the individual presentations enjoyed full concentration, greater financing, and more efficient curatorial screening.

The Cuban participation in the Venice Biennial has provoked many controversies. While extreme radicals protest that those efforts “betray” the fundamental principles of the Havana Biennial and other national events, others insist on considering alternative participation, more or less numerous, more or less tendentious, more or less exclusive.

Liudmila & Nelson / La Isla – Absolut Revolution / 2012 / Videoproyección

Our Biennial is one of the most audacious cultural events of the Revolution, which radically reconfigured the concepts of contemporary art, called the attention to many new names of strange calligraphies, and, most importantly, created a new organizational and curatorial model to visualize and appraise the art of the least favored, as alternative to the market and to the trivializing trends of the hegemonic power. But that strategy of the Havana event, tending to validate a path against the current, never presumed the isolation or negation of the validating role of other world events, whether from the “north” or the “south”. Llilian Llanes herself, founder and director from 1984 through 1999, established relations with countless biennials, museums, foundations, and international institutions of various kinds. In the particular case of Venice, a productive collaboration was maintained with several of its curators including Achille Bonito Oliva, Harald Szeemann, and María Corral.

As a result of these efforts by the Ministry of Culture, the art and artists of the Island have recovered the possibility of a systematic, autonomous Cuban presence in the Venice Biennale, organized by our own curators and specialists. Just like all human work, it is improvable and sensitive to all kinds of questions and dissatisfaction. The fundamental responsibility of our institutional system today is to maintain that conquest by delineating a future strategy tailored to the particular concepts and circumstances of those who now have this course in their charge.