Por: Pérez & Del Valle

What was your experience in the Cuban pavilion of the 57th Venice Biennial?

This is my first time at the Venice Biennial. I always wanted to participate here, but for one reason or another it had never happened before. It coincides with Cuba’s first participation with an independent pavilion.

I was certainly pleased to have been selected to be part of the Cuban exhibit because, even though it involved a lot of sacrifice, I managed to do what I thought was appropriate for this occasion. I wasn’t interested in presenting just another piece or in making a modest effort. I considered it a major project in every sense of the word. Of course, if I have chance to do it again I would try to do it better, but I am very happy with the outcome.

On the other hand, since I had the opportunity to remain several days at the exhibition after setting up my piece, I saw that it worked as an element to draw attention to the pavilion. When entering the library the visitor found an excellent exhibition, very well conceived, and expertly assembled. We were lucky to have a great installer like Quique, with a super efficient work team.

I wouldn’t say the exhibition was insuperable. But it undoubtedly exceeded the expectations I had for this kind of participation in an event such as Venice, and in my opinion it had great dignity, elegance, and professionalism. I am usually wary of exhibitions that are too wide ranging and involving large numbers. I’ve had the experience of organizing some projects, and when there are more than twelve guest artists it becomes very complicated to create a coherent and efficient language among them and for the public. Add to it the many different personalities, each one with his ego, and each one’s conception of art and the space.

Although I couldn’t set up my piece in time for the opening and, somehow, I missed that moment, once it was mounted in Saint Mark’s Square we exceeded the 15 days we requested, and it stayed there 45 days until the rest of the exhibition was dismantled.

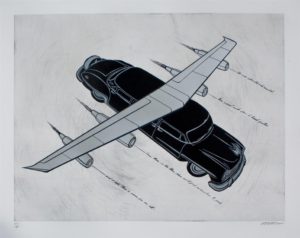

Esterio Segura. Híbrido de Chrysler / 2003 / Limusina New Yorker 1956 y acero / Dimensiones variables

Your piece had been exhibited previously in Cuba and in the United States. How did it work in a space like Venice, where normally there are no vehicles on wheels?

In fact it became a very exotic object. Not only did it have the hybridity of a car with wings, the mixture of its Cuban and American origin added to the interest in the midst of our complicated political circumstance for the last sixty years, aggravated these days in this new situation which is a very complex diplomatic relationship; like a different kind of cold war.

Under the present circumstances, the concepts of travel, immigration, communication, and interpersonal relations have become problematic, not only for us Cubans. From the point of view of the universal situation faced by the human beings, the possibility of movement becomes complex in every sense; not just physical but conceptual and theoretical. This reflection was reinforced to the same extent that the public could wander around to see what was behind the work, but the essential attraction was the peculiarity that in no other place in the entirety of Venice was there an automobile; neither Russian, Cuban, French, German or English . . .

Some European countries have a relationship with Pop culture that we could say is xenophobic, predisposed to the initial surprise of the image and more in favor of the conceptual piece in its most intimate degree. But Venice brings together a very diverse public, which leads to a very varied assimilation. My work has been conceived for all audiences, to both take a picture and remain reflecting on it, with all the nuances in the dissimilar levels of understanding. Many children in Venice had fun playing around the Chrysler and having their picture taken next to it, while other people remained in the square for hours. The public even helped me mount the wings. I received many opinions, emails, phone calls . . . that experience of international assimilation is very important.

I started in the 1990s doing a type of work that had many references to my country and my context, closely related to the formation of Cuban culture; influenced by the research undertaken by Fernando Ortiz, by the history of religions in Cuba, by the evolution of our eclecticism. Without distancing myself from the origins, I tried to develop little by little toward not a universal, but an international view of the language of art in general. That is why I have been moving and have reached the point where I have remade works where I only intervene conceptually, that is, selected objects created from other found objects. In other cases my productions have been marked by foreign influences such as the Bauhaus and Pop. I have tried to create a sort of international Braille for my pieces.

No matter how it happens, when the public understands and reflects on a piece, it leaves a mark on you. Do not assume that things are going well, but at least you are speaking and communicating, which is the most important part of making art. I think that making a piece and leaving it untitled is almost a sacrilege, because if each piece you make really has an idea behind it, then titles are like a courtesy for the public, a door for them to come in and catch a clue.

Esterio Segura. Híbrido de Chrysler / 2003 / Limusina New Yorker 1956 y acero / Dimensiones variables

How did you perceive the Biennial as a whole, and how did you understand the relationship between the problems addressed in the event and those posed in Tiempos de la intuición (Times of Intuition)?

In spite of not having been invited before as an artist, this is the third time I have visited Venice during its Biennial. This edition was a very poor one and did not fulfill my expectations of independent efforts because, in fact, the Biennial exists with the effort of each one of the countries. Just to mention a few, the United States Pavilion, intentionally or not, was a disaster. In the case of the German Pavilion, (which won the Prize), I was scared to see what happened to the conceptualization. I don’t know if it is lost or has disappeared. It seemed to me that the attempt at conceptualization was too simple and at the same time sophisticated. In fact, I believe that art should reduce the level of abstraction from reality, out of respect for the human being. We are reaching a state of the art that is too arrogant toward the public.

I think the Italian Pavilion was very primitive. I entered many spaces and then went out because they did not interest me. Many works were excessively naive. I may, of course, be wrong.

Esterio Segura. Híbrido de Chrysler / 2003 / Limusina New Yorker 1956 y acero / Dimensiones variables

On the other hand, the policy for space in Venice for its Biennial was almost massacred by Damien Hirst’s exhibition. In addition, he copied the work of an artist who happened to be invited to the Biennial. A Hollywood-like, colonialist copy that filled two of the event’s largest and most attractive spaces. I think it’s correct that artists create great productions, but I think that this one somehow was disrespectful and excessive. In addition, with certain exceptions the pieces were more like theatrical sets; very large but primitive. That’s my judgment as an observer.

The fact that Cuba had this large pavilion is also a challenge for the next Venice Biennial. How can we solve this next time? How do we climb another rung?

The norm in the Biennial is to have central thematic showcases and national pavilions, where generally one or two artists are invited. Cuba prefers a group project, in opposition to this practice . . .

I am not in favor of large rosters. Not just because of the problems dealing with different artists, but because I think it may not be efficient to display the vision of Cuban art in very diverse ways. This doesn’t mean that if you choose five or eight artists they will dictate the parameters on Cuban art, but they do make it possible to have a stronger presence; the artist focuses more and I think he receives a certain courtesy. It makes a difference to select 14 rather than 9. Ever since I saw the preliminary list I asked myself if they were sure of that group.

It’s very difficult to put together so many languages, so many ways of making art the same exhibition, particularly if you are short of time to conceive it. Many artists have always have done work, they live in a constant biennial; in my case I feel as if I am creating my thesis all the time. Somehow, many are permanently ready for any event of this kind. Even so, it works better if you have time to produce and organize yourself for a specific space. We should not forget that it is the oldest biennial in the world; it invites you and obliges you to show respect.

Esterio Segura. Híbrido de Chrysler / 2003 / Limusina New Yorker 1956 y acero / Dimensiones variables

Does Cuban art connect with the best things you found at the Biennial?

The work of the Cuban artists in the National Pavilion had a sense of soberness, with a lot of temperament and elegance. And in other cases they were integrated into the type of language and discourse with which the public is familiar. It appeared organic to me. I think that, even if it hadn’t been organic, we enjoy a very special circumstance that we are lucky to experience. Cuba is different; it is not an ordinary country. Creating is a permanent training for us, whether or not you’re an artist. That makes us special and arouses great curiosity. Even when the references for a Cuban artist were not the Island, the public looks for and eventually finds a connection with the context.

I think that contemporary Cuban art, particularly of the youngest ones, has many international references. I could mention Chino Novo and Yaque, whose languages articulate perfectly well with the rest of the international artists working with Continua. This support undoubtedly helps them achieve a language that may flow within the style to which a certain audience is accustomed.

In this sense let us say that there was certain coherence. In spite of the rigor particularly in the Biennial’s central group exhibitions, there were very diverse and too banal works to face a serious public. I favor the dialog with the piece, but not the excessive game that turns it into a mere silly toy. Game Boy and PlayStation moved us forward. Very often, trying to apply the technology to the piece, you achieve the same thing as when you attempt to make a performance without knowing anything about the theater: making a fool of yourself. Precariously, we discover a formula that might be attractive, but of which we have a very rudimentary or elementary knowledge.

Foreigners connect immediately with anything coming from Cuba and turn it into an object of research, reflection, and dissertation.

Esterio Segura. Híbrido de Chrysler / 2003 / Limusina New Yorker 1956 y acero / Dimensiones variables

Esterio Segura. Híbrido de Chrysler / 2003 / Limusina New Yorker 1956 y acero / Dimensiones variables