Pérez & Del Valle

I had already learned about that experience through my brother Yoan, who attended a previous edition of the Biennial, but I had never been to Italy or to Venice. It was a very strong cultural feeling. I visited many exhibitions and pavilions. Being in the pavilion of one’s country with colleagues and artists you admire is very gratifying and impressive.

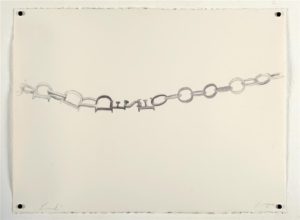

En primer plano la obra Dislexia. 2003 – 2016. Objeto, Metal, y en segundo plano la obra Link. 2014. Objeto, Metal

You participated with already well-known pieces, although I suppose you had a preconceived idea of how to set them up in the space.

The choice was virtually yours and Noceda’s: only three pieces. It somehow connected with my exhibition at the Center for the Development of Visual Arts. A harmonious dialogue was created among them because they shared the material, the use of texts, the forms, and they work in some way as an installation. When I arrived in Venice they were not yet working in my space, so I had time to think and arrange how to distribute the pieces.

The pieces belong to different periods of your work . . .

That’s effectively true. Sometimes bronze techniques greatly prolong the work process. For instance, No Rear View Mirror belongs to a 2009 exhibition in Galería Habana. At that moment I only had the drawing, which I did not even exhibit. I only managed to produce it in 2016, and integrated it to the showcase in Centro de Desarrollo. Link is a relatively recent piece. I presented it as a collateral entry for the most recent Biennial (Zona Franca), but did not have time to produce it in bronze either. The basic idea for the piece with the oil goes back to 2003. This is a remake I started for an exhibition in Daros that ultimately did not take place.

Dislexia. 2003 – 2016. Objeto, Metal

How did you relate to Venice and its Biennial?

My first relationship was with the pavilions in The Gardens, where the event originated. There you find the classic pavilions that each country built at one point. For example, Brazil has a very concrete design; Australia has a very distinctive one . . . but that mixture works very well in that huge garden. I had seen images of pieces by Robert Rauschenberg or Clase Oldenburg, but actually seeing the works was impressive. Sailing in vaporettos to see exhibitions . . . a crazy experience.

I also visited The Arsenal, a huge area that I didn’t get to see completely. I found very interesting works in its relation with space. I was impressed by Philip Guston’s showcase at the Museum of the Academy. I only knew him from books and it made a great impression.

You were commenting earlier about Damien Hirst’s expo . . .

It was immense. Later I found out that it continued on the other side of the bay. I only saw the central area, where the giant was. Hirst attracts my attention because of the great display he makes. However, I think the pieces have fallen into a sort of trivialization in the style of Warhol. I am not evaluating one work and the other, but in general their way of “getting into” art.

The way he fills the space is very clever; even the Grassi Palace bookstore contained his books, catalogs, and souvenirs almost exclusively. He’s like a capitalist octopus, but from art. I don’t want to say that that interest in occupying the spaces is bad, but not in such egocentric and excluding way. On the other hand, the curatorship was fine; some pieces worked better than others. He has fallen into a sort of figurative abstraction, if that exists.

Link / 2015 (Enlace) / Grafito y tinta sobre cartulina / 56 x 76 cm

How do you perceive Cuban art with regard to the proposals of the Biennial?

I think we’re doing very well. The viewers seemed to be very pleased. As a rule they first visited the upper floor: Diago, Yaque, Fors, Wilfredo Prieto . . . and then the space where my work was located. Many had the Caribbean clichés and colors in mind and were surprised. Later I saw many references, photos . . . on Instagram, and there was a great follow up among the public that visited us.

That is also my personal experience. Since the 1980s, Cuban art has been increasingly integrated with international trends without losing its contextual relationship. That is true conceptually and formally.

The Venice trend is consolidated in national pavilions with one or two artists. A group exhibition like ours, with 14 artists seldom occurs . . .

It was a successful, inclusive strategy. It is a world trend to limit rosters: editorials, museums, curators come up with the 10 curators or the 100 artists of the 20th century . . . That is global capitalism: to declare the non plus ultra, to say to us, “This is the guy” and everybody has to pay tribute only to him. They are commercial strategies that I do not judge, either. But I think that presenting this project is very valid for Cuba. Certain Cubans who were visiting commented that Cubans always exceed themselves; featuring so many artists when other countries only present one. But it didn’t seem wrong to me. If the Biennial allows it, every entry must defend his strategy.

That has to do to some extent with imitation. If the first world has resources to present many artists and only presents one, why then does Cuba do something else? It didn’t bother me . . . maybe it’s because I was included.

Projects that derive from this participation in Venice . . .

Lorenzo Fiaschi from Galería Continua was there and invited me to the project for the tenth anniversary of Les Moulins. I will send the pieces from Venice, along with others they added from here in Havana. It will be an exhibition with some twenty artists, not only the ones the Gallery usually works with. That could have been influenced by the conception of our Venice pavilion.

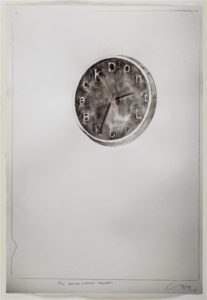

No rear view mirror / 2015 (No hay espejo retrovisor) / Grafito, lápiz de color y tinta sobre cartulina / 100 x 70 cm